On March 1, 2018, Louisville Visual Art will present WIlma Bethel with the Art Educator Award, in memory of Anna Huddleston. Former LVA director John Begley remembers the influential artist and educator.

“. . . (African American artists) run around, do good things and then disappear.” - Fred Bond, a Louisville Black artist, colleague, and friend of Anna Huddleston

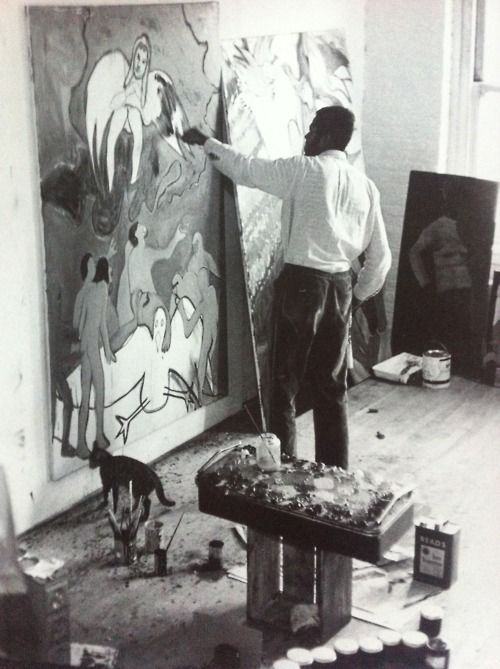

Photo courtesy Ed Hamilton.

Anna Huddleston was a force for art education in Louisville for many years. Beginning as a elementary art teacher in what were, in that period of segregation, referred to as Louisville’s "colored" schools, then as a middle school teacher at DuVall in the integrated Louisville Board of Education, and finally as the Resource Art Teacher for the Jefferson County Public School system, she mentored and encouraged many students, beginning instructors, and emerging artists. She was also president of the Kentucky Art Education Association.

After retirement, she continued her community engagement in many ways, working to establish the Louisville Art Workshop with fellow Louisville artists G.C. Coxe, Fred Bond, and Ed Hamilton, and serving on various boards including the Bourgard College of Art and Music, and the Art Center Association (now the LVA) where she was deeply involved in expanding the free Children’s Fine Art Classes (CFAC) into new neighborhood venues, including the West End.

Generally working behind the scenes, she received deserved recognition in Black Kentucky artists: an exhibition of work by black artists living in Kentucky that was organized for the Kentucky Arts Commission and toured by them from June 1979 through January 1981, and shortly after when she was the first African American artist to be awarded the Kentucky Arts Council’s highest honor, the Milner Award, at that time the only Governor’s Award in the Arts in Kentucky.

Ed Hamilton, Anna Huddleston, Gretchen Bradleigh, William Duffy, & Sylvia Clay. Photo courtesy Ed Hamilton.

With the Stars Among Us luncheon on March 1, the LVA will again remember the important achievements of this landmark visual arts educator so that her contributions to following generations do not disappear.

John Begley is a Printmaker, Installation, and Video Artist. From 1975 to 2014 he was a Curator and Gallery Director, including 19 years as Executive Director of LVA and several years with the UofL’s Hite Art Institute, where he is now Coordinator of the IHQ Project.