“Thompson was in a class nearly by himself in recognition in the world of art. Not until the emergence of Jean-Michel Basquait in the 1980s would another African-American be so embraced.” – from the African American Registry (AAReg).

On March 1, Louisville Visual Art will award Vinhay Keo the 1st Annual Rising Star Award. The award is meant to recognize a young artist who seems poised to have a more widespread impact in the world of visual art. It honors the memory of Louisville-born artist Bob Thompson, and cites his career as an example of exactly what it might mean to be labeled, “rising star.”

Thompson was born in Louisville but came of age in Boston, where he had been sent to live with relatives after his father was killed in an automobile accident. He entered college as a pre-med student, but increasing depression over the loss of his father left him troubled and unsatisfied. Seeking to alleviate his grief, he returned home to enroll as an art student (with a scholarship) at the University of Louisville in 1956.

According to his entry in Smithsonian American Art Museum, his natural talent and enthusiasm prompted legendary U of L Professor Mary Spencer Nay to encourage him to spend a summer in Provincetown, Massachusetts:

“There were two important art schools in the old fishing village of Provincetown—the Seong Moy Art School and an older, more established institution under the direction of Hans Hofmann, the innovative abstract expressionist painter. One of Hofmann's students at that time was the young artist Jan Müller, who departed from Hofmann's aesthetic principles of nonobjective painting in favor of a figurative style.

Provincetown was an exciting environment for Thompson, and he was especially attracted to Müller's figural paintings and the works of Red Grooms, from Nashville, Tennessee. Grooms was also involved in performances that were later called "Happenings" and represented a new aesthetic concept. Thompson was an active participant in many of Grooms' productions.”

Conventional wisdom for the Louisville artistic community has often held that you have to go elsewhere to “make it”, but Thompson’s story is more fluid than that canard. Coming home was clearly a crucial step in his life - its how he found his true path, yet it also was, in a very short time, the springboard for him to emerge again into the larger world of American Art.

He married Carol Plenda in 1960, and a Walter Gutman Foundation Grant and a John Hay Whitney Fellowship enabled them to spend the first two and-a-half years of their marriage in Europe. Upon their return, Thompson joined the Martha Jackson Gallery, where all of his exhibits made a sensation, and he sold consistently well: his work was purchased for the permanent collections of prominent museums like the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the National Gallery of Art.

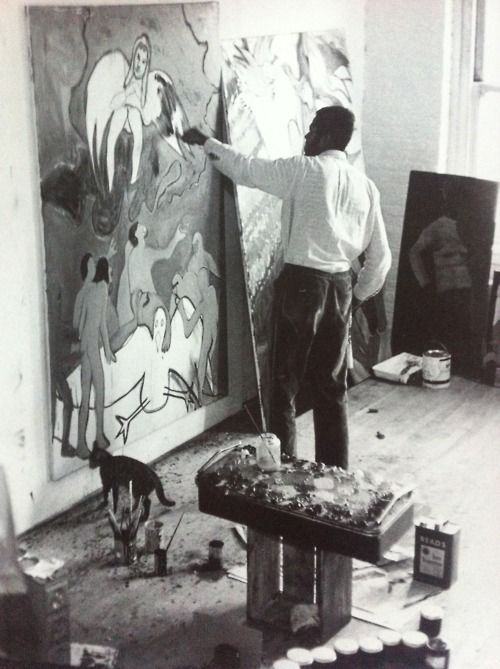

Thompson’s paintings range from a large-scale, gestural abstract to a more figurative expressionism. He drew obvious inspiration from the old masters he had studied firsthand in Europe, forming compositions of biblical narratives and classical mythology rendered with an expressionist’s sense of form and color.

"Stairway to the Stars" by Bob Thompson c.1962, oil and photostat on Masonite, 40x60in, © Estate of Bob Thompson

As part of the Hite Art Institute’s 75th Anniversary Celebration, the University of Louisville mounted an exhibit in 2012, Seeking Bob Thompson: Dialogue/Object, which was curated by Hite Art Institute Gallery Director John Begley (now retired), and Slade Stumbo, who at the time was finishing his Curatorial MFA at Hite.

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC is the exclusive representative of the estate of Bob Thompson. Since 1996, they have presented four solo exhibitions of the artist’s work, and published catalogues for three of the shows. Most recently, the gallery presented Naked at the Edge: Bob Thompson in 2015.

Permanent Collections: (select) Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago, IL); Brooklyn Museum (Brooklyn, NY); Chrysler Museum of Art (Norfolk, VA); Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art (Bentonville, AR); Detroit Institute of Arts (Detroit, MI); Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution (Washington, DC); The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, NY); Minneapolis Institute of Art (Minneapolis, MN); Museum of Contemporary Art (Chicago, IL); Museum of Fine Arts (Boston, MA); Museum of Modern Art (New York, NY); Nasher Museum of Art, Duke University (Durham, NC); National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC); New Orleans Museum of Art (New Orleans, LA); Philadelphia Museum of Art (Philadelphia, PA); Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington, DC); Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (New York, NY); Speed Art Museum (Louisville, KY); The Studio Museum in Harlem (New York, NY); Tougaloo Art Collections, Tougaloo College (Tougaloo, MS); Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art (Hartford, CT); and Whitney Museum of American Art (New York, NY).

“Le Roi Jones and his Family” (1964) by Bob Thompson, oil on canvas, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (© Estate of Bob Thompson; courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

"Untitled (Michelangelo's Fall of Phaeton)" by Bob Thompson, 1963, gouache on paper (page from art catalogue), 12 1/8x8 3/4in, signed and dated, © Estate of Bob Thompson

"The Judgement" by Bob Thompson, 1963. Oil on canvas, 60x84in. Brooklyn Museum, A. Augustus Healy Fund, 81.214. © Estate of Bob Thompson (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 81.214_SL1.jpg)

Written by Keith Waits.

In addition to his work at the LVA, Keith is also the Managing Editor of a website, www.Arts-Louisville.com, which covers local visual arts, theatre, and music in Louisville.